Article by: Alva Rosengren, Angèle Duplouy, Athanasia Dordokidou, Matteo Scannavini, Mireia Jimenez Barcelo

The EU Commission is trying to implement a just transition “leaving no one behind”, but local bodies, such as trade unions and municipalities, are concerned about the lack of consultation risking the future of workers.

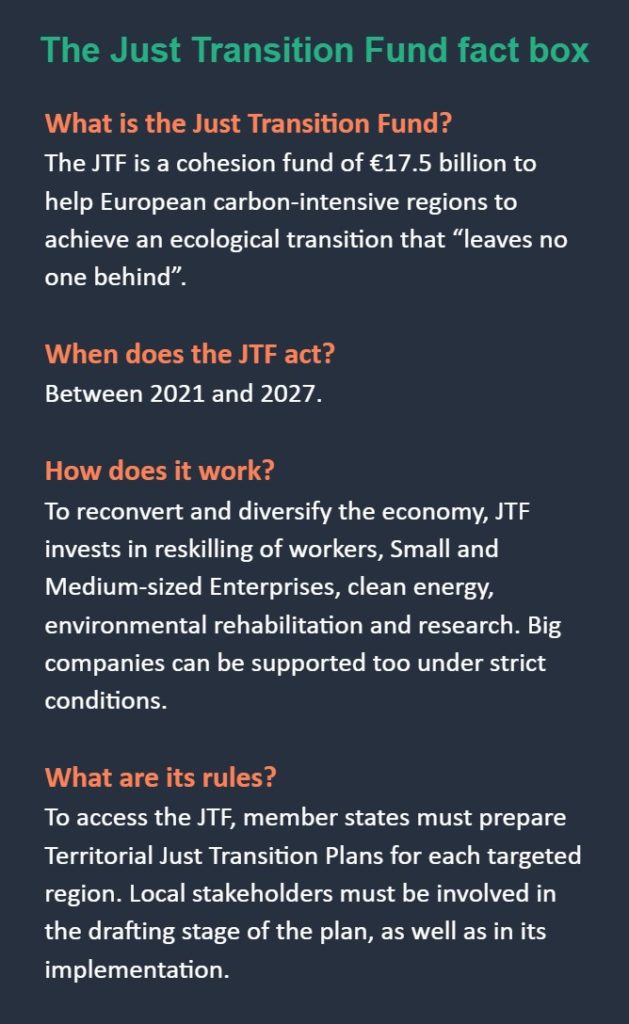

By the end of 2022, every member state but Bulgaria finalised its territorial plans to access the Just Transition Fund, the €17.5 billion fund helping carbon-intensive regions towards a sustainable energy transition while balancing thousands of job losses.

“The transition will happen. It’s a question of managing it or being managed by the transition”, said Francisco Barros Castro, cabinet expert of the European Commissioner for Cohesion and Reforms Elisa Ferreira, explaining the EU is providing funds, rules and assistance, but it is up to member states to make the best use of it.

While some countries are at the forefront of JTF implementation, others stay behind, challenged by the nature of their job markets and a lack of communication with their territories and local entities.

A neglected partnership principle

According to JTF regulation, the partnership principle is one of the pillars of the just transition, meaning local bodies must be consulted during the plans’ drafting stage and through a monitoring committee in its implementation. However, despite what is reported in the territorial plans, discussions with local stakeholders are not always carried out properly.

This is the case in Italy. “The involvement of the trade unions does not exist today and never has” stated Emanuele Madeddu, the secretary of the union Filctem CGIL of southwestern Sardinia. The Sardinia region arranged a few consultations with the territory in the Spring of 2021, aiming to define just transition guidelines with local stakeholders. However, Madeddu and other unions described the meeting as generic and “without a real discussion to build together the intervention plan for Sulcis”.

Since then, very little communication about the JTF has occurred between the region and the local bodies, causing concerns. Ignazio Locci, mayor of Sant’Antioco and president of the Union of Municipalities of Sulcis Archipelago, reported “We don’t know anything since the consultation phase”. Other local mayors like Andrea Pisanu and Stefano Rombi described the events as two years of “total darkness”.

Last fall, the case of the Sulcis trade unions was brought to the European Commission by the Green MEP Ignazio Corrao. Despite the dissatisfaction with the initial consultation, from May 16th trade unions became involved after their inclusion in the national monitoring committee of the JTF.

Consultation is lacking also in Spain due to the dynamic between the centralised Institute for Just Transition (ITJ) and the autonomous, self-governed regions. For instance, while in the north region of Asturias, the JTF was introduced to some social bodies, in the Balearic Islands the local government only offered one general meeting communicating all just transition plans, national and EU-funded, three months before the JTF was nationally approved.

Either way, trade unions and environmental groups do not seem to act as participants defining the fund’s performances in every region, as the regulation states, but only as spectators of already-defined plans with local governments and companies.

“We have not participated as parties involved in defining these actions (…), the ministry has spoken directly with the regional governments and companies without speaking with the logical trade union structure representing workers,” said Vicente Sánchez, a representative for energy transition in the trade union Comisiones Obreras (CCOO).

During the implementation process, Greece failed to be inclusive. Initially, all projects were led by the Ministry of Environment and Energy which was collaborative and effective, but later were transferred to the Ministry of Development. As Nikos Mantzaris, member of the Committee on Climate Change Mitigation pointed out, “Since then, there has been a top-down approach. It’s not just an administrative change, it also puts a stop to any cooperation with anyone else”.

The European Commission is aware that “In some cases, there was less consultation than ideal”, as commented by Francisco Barros Castro, policy expert of the cabinet of Commissioner Ferreira. “On the other hand, – specified Castro – we would not accept a territorial just transition plan if we were not satisfied with the consultation process.” He also presented tools the EU is providing to give more visibility to regions and stakeholders, such as the Just Transition Platform Conference, a periodical meeting to share experiences with JTF between member states.

In contrast to the Commission’s position, JTF Rapporteur Siegfried Mureșan said that the EU Parliament has been asking for stricter control of state consultation with local bodies and stakeholders. “We want governments to be obliged to consult stakeholders. We want the European Commission to evaluate this and we want, if the evolution of the Commission is negative, a plan to be rejected unless it is improved.”

He claimed this was the Parliament’s vision for the Recovery and Resilience Facility, but the EU Council was against it because countries want money with “no rules and with no obligations”.

“This is a fight where we [EU Parliament] are always very demanding, the governments don’t want to do anything and we have to push.” he said.

As the European institutions are putting regulations and funds, it is up to national and regional governments to really involve their territories in implementing an effective and fair transition. Should they fail, the JTF will only throw money at the problem and not avoid thousands of job losses.

An inconsistent job market

The green transition will have a large impact on workers of carbon-emitting industries. Many municipalities in Norrbotten and Västerbotten, the northern regions of Sweden, have struggled with a decreasing population since the 1980s. The green transition of the steel and metal industry, as well as the money from the JTF, will create a high demand for human capital resources. With a relatively low tax capital, the regions stand before a great challenge to develop housing and infrastructure, and cannot afford to bring expertise from elsewhere in Sweden.

Rikard Eriksson, professor in economic geography at the University of Umeå, is leading a study of green industrialisation in northern Sweden. “A green transition of the industries is not actually sustainable if it doesn’t include the rest of society.” he explained.

Ylva Sardén, senior advisor for the region of Norrbotten, emphasises the challenges of future regional development. “We are simply too few people to solve it. Pure capital would perhaps not solve the problems, but it is clear municipalities are on their knees.” she states.

In contrast, the south of Europe is facing a different challenge. Trade union representative Vicente Sánchez, also a doctor in applied economics at the Universidad Complutense in Madrid, explained how jobs in the renewable sector are less and of lower quality than those being lost in coal mines and energy plants.

“The salaries in these sectors are much lower than those received before. (…) Moreover, maintenance does not necessarily have to be carried out by personnel based in those regions, it can come from neighbouring areas. Therefore, we are not even guaranteeing that workers stay in those regions.” Sánchez explained.

Solar energy is booming in Mallorca, where the tourism industry’s energy demand and the definite closure of the coal plant of Es Murterar are fostering new investments in renewables. However, in April 2021 five Mallorcan ecological groups published a press release denouncing how the mass instalment of solar fields in the island lacked territorial planning, which is required according to the new Spanish Climate Change and Energy Transition law of 2019. To this day, no territorial planning has taken place, and in 2023 the island will be hosting more than 60 solar fields, some of them holding up to 10 hectares, while protests are already taking place in some villages around the island.

Margalida Rosselló, representative of Mallorcan environmental group Terraferida, which participated in the press release, also added how job insecurity is a problem when installing these fields. “Companies are interested in renewables because there is financial aid. They install it in a certain place and then they start an energy-selling process for 25-30 years. This barely creates any jobs (…) There are jobs when building it, but when they are already built after a year there will be one or two jobs since it’s all digitally monitored already.” she said. The JTF will invest €2.1 million in solar energy in Mallorca alone.

The same issue also affects Italy, where trade unions of the metal and energy industries claim new green jobs risk being short-term and not enough to cover future job losses.“Workers will build photovoltaic systems, but what will happen then?” asked the secretary of union FSM CSIL Giuseppe Masala “It would be different if those solar fields were built and recycled in our territory”.

Furthermore, another concern of unions is the vagueness of the current ideas of reskilling, which are likely to struggle considering workers in Sulcis are 55 years old on average.

When it comes to job losses, various programs have failed so far in Greece. Nikos Mantzaris, member of the Committee on Climate Change Mitigation, stated that “There are some resources, approximately 120 million, that have been activated for the purpose of reskilling and up-skilling, but the absorbency of these resources is alarmingly low”.

As a Senior Policy Analyst of GreenTank, he said a study in 2020 found there is a profound ignorance in Greek society, across all ages, regarding the green transition. As he mentioned, things have only gotten worse over time. Few trade unions and local communities have shown interest in whether the transition is progressing.

The transition of the job market is thus facing different challenges in North and South Europe, ranging from not having enough people for new green jobs to struggling to ensure training and employment for all. Despite these difficulties and risks compromising the potential of JTF, some countries have already managed to start a successful transition.

Where the JTF is working

In comparison to other countries, Sweden managed to come far in the implementation of the Just Transition Fund. So far 19 projects, a total of €20.5 million out of the planned €156 million, have been approved. The purpose of the projects ranges from competence development in the job market to studies on technological advancement in the steel, iron and mineral industries.

“Despite the challenges the region is facing, we are very happy and grateful for being included in the fund,” said Ylva Sardén, senior advisor for the region of Norrbotten.

Despite a lack of projects in Silesia, other JTF regions in Poland are at the forefront of implementation, with regions like Eastern Wielkopolska showing one of the most progressive territorial transition plans in Europe.

“For me the exciting thing is actually seeing how the ambition is increasing with each year” said Stępień. “The monitoring committees for the five regions included are all on the voivodeship [regional] level (…) it hasn’t been centralised, which is actually very good. It’s closer to the region.”

Similarly, Greece and France have successfully included local bodies during the planning process. For instance, local bodies in the region of Western Macedonia contributed significantly to the final plans. According to the regional governor, Georgios Kasapidis “From the beginning, all municipalities showed interest and submitted their proposals”.

The European Commission has also been successful when implementing the plans in Poland. “They’re interested in what we have to say about what’s happening in the regions because they know we actually work there.” Stępień added.

“Every single member state but one [Bulgaria] has now clear plans for phasing out fossil fuels and cleaning up high-polluting industries,” said Castro, mentioning the Netherlands, Sweden and Estonia as countries where projects have already successfully started. “Romania had no plans for phasing out coal, even though mines were closing every year or struggling […]. We have 76 regions and in most of them actually the just transition plans are working very well”.

Good examples around Europe show that the huge ambition of converting the carbon economy leaving no one behind is more realistic when EU institutions, national and regional governments and local stakeholders work together. As the just transition has only taken its first steps, the monitoring of the implementation of the JTF in the next years will be crucial to ensure a steady future for the workers of all European carbon-intensive regions.

This article is the second part of an investigation of the EU’s Just Transition Fund

and part of “Crossborder Journalism Campus”, an Erasmus+ project of the

University of Gothenburg, Leipzig University and Centre de Formation des Journalistes in

Paris. Additional reporting: Laura Lansche, Manon Krakowiak, Sophia Seifert.

See our social media video here.