Photo: Jan Ainali

When an international student lacking a “personnummer” needs urgent help, who ought they turn to? “When a student becomes ill, there is currently uncertainty as to whether the student should turn to primary care or a student health clinic” states SFS (Swedish National Union of Students). In this article, we will explore the stories of international students who struggled to access healthcare in Sweden.

I was a one-year non-EU student at the University of Gothenburg. Early in my first semester, I experienced culture shock and stress from my studies, and I decided to seek help as it affected my studies. I could not find assistance on my University’s website, so I turned to my professor. She directed me to Feelgood–the University’s healthcare provider. But contacting them turned into a weeks-long back-and-forth that lasted longer than my own health issue. The problem stemmed from them asking me for my “personnummer”. I did not know what that was, and providing them with my name was insufficient. So I never received help from them.

A “personnummer” is an ID number the Swedish state provides through Skatteverket (the Tax Agency). It serves as an identifier in databases and most services in Sweden are linked or limited to having a personnummer. EU students can get a personnummer, and non-EU students can also get one through a longer process. However, non-EU students can only get one if they are here for a two-year (or longer) program. Not possessing a personnummer, though, can limit a person’s access to services in Sweden, even healthcare.

The second time I needed healthcare, I had kidney pain. I did not turn to the University because they did not help me the first time. I was laying down at University, not able to move. I called for an ambulance, but when I could not provide them with a personnummer, the operator said they could not send one to me. After convincing the operator to send one, it arrived half an hour later. By this point, I had been in pain for a long time. When the first responders came, they asked me for identification again before helping me, but I could not talk. They gave me two Iprens and showed me the closest vårdcentral to walk to. They did not want to drive me, but I could not walk. They told me to order a taxi instead. After convincing them, they eventually drove me. Even though I made it to the vårdcentral, and the doctors helped me, they never treated my illness or pain. I had to visit seven other hospitals and clinics and never got treatment for my illness. At this point, I asked myself if other students underwent something similar to me or if I was unlucky.

“A personnummer is a golden key to Swedish society.”

– From Difficult to Live without Personnummer by Elin Schwartz.

On the front page of the University of Gothenburg’s website, there is no direct link to healthcare-related assistance, nor is there any information about Feelgood. Instead, it is buried under two subpages. The website states they help students with study-related health issues. Still, many students turn to teachers for help.

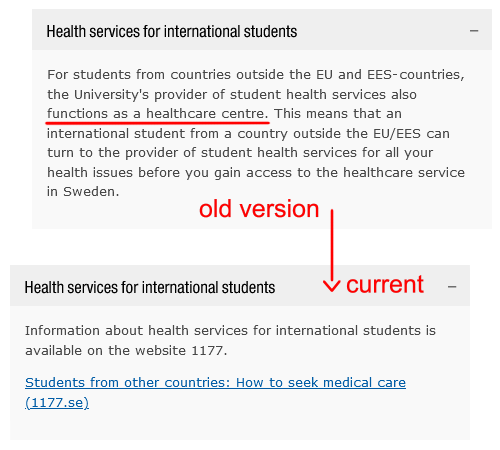

Photo: Anna von Brömssen

The University of Gothenburg’s website asserted that the university’s healthcare provider would work like a clinic and treat international students. That was not factually accurate, as they are not legally allowed to. The inaccurate wording on the website was only updated and amended recently. According to lecturer and MIJ coordinator Ulla Sätereie, international students with mental or physical issues regularly ask her for help, and she guides them to Feelgood as the old website promised to help. An archived version of the old website can still be found here. According to her, 1177 does not provide enough information for international students. She stated: “[W]e like international students.” She acknowledged that students without personnummer are vulnerable: “[W]e have to provide them [with] a better healthcare system.” The University of Gothenburg was the third most commonly applied university in Sweden in 2023.

Students’ stories

One EU student who contacted us explained how the language barrier and lack of a Swedish phone number made it difficult for them to contact healthcare facilities here. They called various hospitals and vårdcentraler in an attempt to book an appointment. But they never received a reply. They realized that the system did not register international or European phone numbers and that it was difficult to acquire a Swedish phone number without a personnummer. They had to ask a Swedish friend to make an appointment for her instead.

Another student recounted their experience of facing difficulties receiving help from therapists. With their Blue Card, they booked three appointments with a therapist at Feelgood after they began experiencing Schizophrenic tendencies. The Feelgood staff recommended the student go to a hospital out of fear for their condition. However, after the hospital visit, the student did not get any replies from their Feelgood therapist and was denied further help.

For 2023, 15,168 people without a personnummer applied to study at a university in Sweden, as per data from UHR (the Swedish Council for Higher Education). We contacted students from universities in Sweden to hear what they had to say about healthcare here. The form includes Swedish, EU, and non-EU students from four universities in Sweden: the University of Gothenburg, University West, Uppsala University, and Lund University. We asked students 13 questions with subquestions and gave them the opportunity to share their experience seeking healthcare treatment in Sweden. So far, 20 students answered the survey, nine non-EU students and 11 EU students.

A non-EU student at Lund University said they went to a vårdcentral for their mental health issue but could not book an appointment there because they did not possess a personnummer. They complained that the information they received from the university did not specify which clinic or where to go to for health-related issues and that there were no doctors available for non-EU students.

An EU student at Uppsala University said their university did not help them when they faced health issues. After visiting several clinics, they said that doctors continuously denied them treatment–even though they had a European Blue Card. They said they were denied after the doctors asked them for a personnummer.

Another non-EU student at the University of Gothenburg said they asked for help from their university twice and received no help. They said they visited vårdcentraler but lamented the poor services they received for not having a personnummer and the long waiting times. The prices were also expensive for them, and they were never reimbursed.

One EU student at Uppsala University said they had paid for insurance and sought physiotherapy help. They said they decided not to take the hospital’s treatment after learning that their insurance would not cover the price for not having a personnummer. They said they had to endure the pain and wait until they returned to their home country to be treated. A program coordinator at Uppsala University reported that students extend their one-year program to two years solely because they would receive a personnummer.

The co-author of this article, Hongyu Zhang, had a toothache and turned to her professor for guidance. They sent her links saying students under 24 are exempt from dental care fees but must be registered. She was confused, did not find further information or help, and never received treatment for her pain.

Although the Swedish healthcare system has received acclaim for its quality and accessibility, international students without a personnummer frequently struggle to receive help. Of all the students surveyed, 12 out of 20 expressed dissatisfaction with the Swedish healthcare system. Considering only non-EU students, eight out of nine were not satisfied. Six out of the 20 students also stated they had to endure physical pain because they did not receive healthcare. Many claimed that not having a personnummer made accessing healthcare needlessly complicated. EU students get EU “Blue Cards”, which allows them to access healthcare in the Union. Despite this, many EU students stated they were still denied treatment.

What the authorities said

Finding responsible people for this issue proved difficult. The government and regional government are responsible for healthcare in Sweden, Migrationsverket for international students, and Skatteverket for personnummer. The university is also responsible for its students. Linda Emanuelsson, working at student support at the University of Gothenburg, stated that finding the people responsible was an arduous task, and finding someone willing to talk to her, was even more difficult. She admitted that many systems in Sweden are not working as fully intended for students. Emanuelsson’s role is to convey students’ feedback to the state, but cannot do so if no one is willing to converse with her.

Feelgood denied us an interview. Emanuelsson clarified that they also offer care for physical injuries, but only if the harm arises from a school activity. For students experiencing a physical injury not directly related to their studies, Feelgood will not help. Three students we have been in contact with stated that Feelgood did not help them with their issues. Emanuelsson explained that the University of Gothenburg chose Feelgood after carefully considering the options and what they offer. If Feelgood is the most suitable healthcare provider for students, why are students not satisfied? According to our form, 16 out of 20 students chose “I didn't ask for help, but I found the way by myself” to our question: “Did [the university] help you, connect you, or direct you to the right person?”

Linda Emanuelsson told us that they are actively seeking ways to improve the help offered for students lacking personnummer but cannot do much if the government does not listen. Everything is tied to the law, so only little can change without legislation. Furthermore, Feelgood does not have a direct way for students to file complaints or give feedback. Students must, instead, turn to their universities, and the university then conveys the feedback to Feelgood. The students can also contact the student unions. This way of providing feedback is very convoluted. Linda Emanuelsson admitted that the appropriate university feedback channels are very indirect and hard to find, so few complaints ever reach the university or Feelgood.

Besides the university, students can also direct their feedback to the Patient Advisory Committee. The Committee “is an impartial group in all regions of Sweden that can help you present your viewpoints or complaints to the clinic or unit in question” and they ensure that the students will receive answers to their complaints. We contacted and asked the Patient Advisory Committee for statistics on student complaints, but they “don’t keep statistics, whether the person is a student or not” according to their Press Secretary.

International students are instead covered by private insurance. At the University of Gothenburg, the insurance provided is FAS and FAS+. On their website, they state that they cover “emergency medical and dental care” and exclude “[r]egular medical check-ups [and] medications”. They do not elaborate further. On another page of their website, however, they state that they do not cover medical emergencies that did not occur “[d]uring school hours” and “in the school premises” or “on the school grounds”.

Photo: Erland Törngren

Similar to the criticism of Feelgood, FAS does not directly take feedback from its users. Instead, students are expected to direct their complaints to the same obscure channels at their university as Feelgood. On a positive note, a spokesperson for FAS, Erland Törngren, assured us that FAS and its partnered universities have regular meetings to discuss improvements to the insurance. Nonetheless, it would be better for both FAS and the students covered by the insurance if there existed a more direct way for students to give their feedback instead of going through their university.

Although FAS and other insurance companies reimburse the students, when a student seeks emergency healthcare treatment, they must first pay for the treatment out of their own pockets before they can contact FAS for reimbursement. That can be an issue for students who do not possess such large sums of money at hand. Nils Pasi Nävert, the Administrative Officer at the Service Center of the University of Gothenburg, acknowledged this and said it is unfortunate that this is the system, but nothing can be done if the law is not changed.

We also brought up the problem of banks with FAS. For persons lacking a Swedish bank account (which is hard to open without a personnummer), they can transfer the funds to their foreign bank. Törngren was unsure whether the foreign banks would incur a transaction fee. So, the final amount the student receives might not be the exact amount they are owed. Alternatively, the student could request the reimbursement as a check, but then they must be physically present in Sweden.

Photo: Fialotta Bratt

Extra-EU international students studying one-year programs do not receive a personnummer per the law. Vjera Catovic, a spokesperson at Skatteverket, explained that a person must have a visa and physically be in Sweden for exactly one year or longer to receive a personnummer. One-year students often receive a visa slightly shorter than that from Migrationsverket (the Migrations Agency), thus prohibiting them from getting a personnummer. Instead, there are student IDs and “samordningsnummer”, both resembling personnummer, but they cannot be used for many services in Sweden.

Possessing a personnummer is essential for living in Sweden. The dilemma is that, since many international students will stay in Sweden and apply for a one-year work visa after graduation, they will be entitled to a personnummer in the end anyway. It would be more advantageous for the authorities to reconsider the laws to approve one-year students to also obtain a personnummer and be better for the students.

What can be done?

The spokesperson for Skatteverket told us that they do not provide one-year students personnummer “not [for] the fear that personnummer will run out” but “provisions in the law”. Despite this, many researchers and reporters have noticed a scarcity of personnummer, which has caused problems, like multiple people having the same number, a different date than their birthday, and confusion at hospitals. Emanuelsson said she “[thought] it would be wonderful if [they] can help international students more”, and said it would be “a great idea” if non-EU students were given a more complete package regarding healthcare.

By the University of Gothenburg students Khorrambanoo Askari and Hongyu Zhang.