Europe’s EV makers play fast and loose with human rights disclosures while EU laws have no traction.

Authors: Fabio Cantile, Gianluca Grasselli, Kelsey Lescop

In early December 2019, Ursula von der Leyen walked onto the EU’s press room stage to announce the European Green Deal. She promised drastic emission cuts and massive investments for innovation before striking an even more ambitious note: “This transition will either be working for all and be just, or it will not work at all.”

Three years later, much of this grand vision remains in the dark. One much-anticipated policy of the Green Deal, the “Green Taxonomy” initiative, was meant to create an official EU green label for investments like stocks and bonds. Companies could make changes to their businesses to earn the label and so attract environmentally conscious investors. But after a rash of political controversies, the policy is floundering.

In 2022, a contentious move to include the nuclear and gas industries under the green label created a political maelstrom, which led to lawsuits from member states and NGOs trying to block the decision. A few months after the nuclear and gas law was approved by parliament, five members of the advisory group which oversees the program suddenly walked out, citing political interference.

“No one wants to hear about the EU taxonomy anymore”, writes Luca Bonaccorsi, one of the former members of the advisory group. “Now everyone avoids it, like an unpronounceable love gone wrong.”

The green labeling program is a labyrinth of technical criteria- It defines “greenness” for businesses from apartment buildings to garbage tips. A new building that protects against climate related floods could earn the green label. A garbage company that installs a greenhouse gas capture system could also call itself green.

In order for an activity to be defined as sustainable, a company has to show that it contributes to one of six established environmental goals, while not harming the other five at the same time. This could mean, for example, that an activity with reduced emissions is green, but not if at the expense of a river or threatening biodiversity.

Companies must also verify that they respect human rights to earn the green label. They promise to follow international guidelines called “minimum safeguards”, which cover issues like child and slave labor, safe working conditions, unionization rights, corruption, among others.

Many companies claim the green label despite sourcing their materials from suppliers condemned for corruption and accused of human rights abuses. This disparity between the grim reality of supply chains and the sunny presentations of companies’ environmental, sustainability and governance reports, usually shortened to ESG, is enabled by a body of legislation which functions more like suggestions.

Photo credit: Afrewatch2020

EVs are the new king of the road in Europe. Sales of fossil fuel cars fell below 50% for the first time ever at the end of 2022, and EU parliament recently banned the sale of new fossil fuel vehicles starting in 2035. “Zero-emission cars will become cheaper for consumers,” says Dutch MEP Jan Huitema. “It makes sustainable driving accessible to everyone.”

But while Europe’s drivers stand to benefit, the same can not be said for the workers who provide the raw materials to build electric vehicles. EVs rely on batteries which often require the mineral cobalt, and seventy percent of the world’s cobalt comes from The Democratic Republic of Congo. Eighty percent of the DRC’s cobalt industry is controlled by a small handful of producers.

One large miner, Anglo-Swiss company Glencore, has frequently been accused of human rights violations. Workers interviewed at several of Glencore’s mines by the human rights and corporate accountability NGO RAID describe dire conditions at the mine sites. Andre, a worker at Glencore’s Kamoto Copper Company (KCC) mine said, “We were working hard, without any breaks, for $2.5 a day. If you didn’t understand what the boss said to you, he would slap you in the face. If you had an accident, they would just fire you.” Andre also claimed that workers were only provided with two small bottles of water per day, “It is quite hot in the mine, so I am often thirsty.” Appeals to Glencore to improve conditions at the sites were ignored by the company.

Glencore has also faced allegations of child labor at its mine sites. An ongoing lawsuit in the USA is seeking damages on behalf of child miners who were severely injured or killed in mining accidents. Investigators who visited the children determined that they had worked at specific cobalt mines which were owned or operated by Glencore.

In 2022, Glencore faced at least six criminal and civil suits for bribery, fraud, and market manipulation. It settled cases in the US, UK, Brazil, Mexico and the DRC to settle allegations spanning ten different countries.

The company has set records for the largest fines issued by the United States’ commodities trading regulator. It was also forced to plead guilty to criminal charges in both the United States and the UK, and agreed to pay the Congolese government $180 million to settle bribery charges. Altogether, Glencore paid at least $2.7 billion in fines and penalties last year alone. Glencore did not respond to inquiries made by the team concerning their Cobalt mining operations.

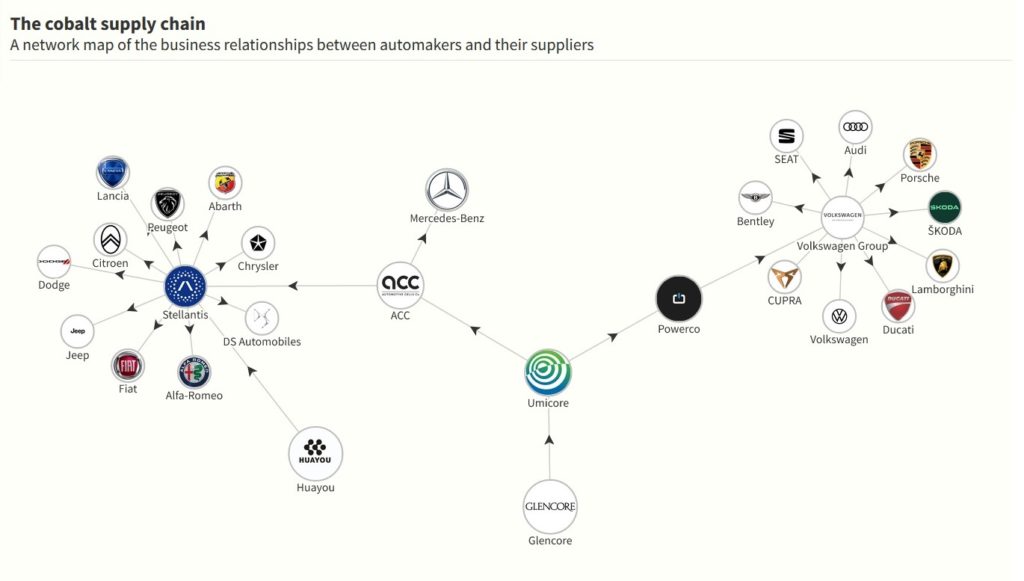

The supply chains that connect Glencore and its Congolese mines to European EV producers are often quite short. In 2019, Glencore signed a deal to supply the Belgian refiner Umicore with cobalt from two of its Congo mines. Umicore later inked a deal with Volkswagen to produce battery parts for Volkswagen’s electric vehicles. Umicore boasted that the planned venture would supply enough battery materials for 2.2 million cars per year by the end of the decade.

Corruption is specifically cited as a human rights violation in the foundational agreements governing the issue, yet neither company mentions Glencore’s legal troubles or possible human rights violations in their ESG reports. According to Raphael Deberdt, a researcher on corporate due diligence and human rights from the University of British Columbia “corruption is a human rights issue. The impact that it has on the DRC is one of the reasons why the country is so poor.”

Companies are able to discreetly overlook these serious problems because the rules governing human rights abuses are vague, general, and have almost no mechanism for accountability. “Who is going to check and say you’re not meeting the minimum safeguards? At the moment, nobody really,” answered Antje Schneeweiss, a former rapporteur for the social aspect of the EU taxonomy program who was interviewed by the team for this story.

Source: company reports and securities filings. Credit: Fabio Cantile

Last October, the EU released a report on the taxonomy program’s approach to human rights and preventing corruption. The report attempts to interpret the definition in the taxonomy law of the minimum safeguards; a definition that is expressed in only two short paragraphs. At one time, the EU had considered drafting its own rules, but high-level authorities were “absolutely opposed to the idea,” according Schneeweiss. Instead, the report advises companies on a potpourri of existing and developing laws and guidelines.

Most of these rules are built on two standards: The UN’s Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights and the OECD’s Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises. Yet, these foundational texts are guidelines, not laws: they are voluntary, there is no penalty for non-compliance, no mandatory auditing, and virtually no enforcement mechanism. They function more like recommendations, encouraging companies complicit in human rights violations to take general steps without specifying exact requirements. “Companies are good at writing papers but that is it. There are no fines or obligations to encourage them to do otherwise,” explains Deberdt.

For companies interested in earning the EU’s green label, they must claim compliance with these minimum safeguards, but the final decision on that point is left to the companies, and in the research for this report, not a single company was found that declared a failure to comply with the safeguards.

Companies comply with the guidelines by writing ethical codes of conduct and giving their suppliers self assessment surveys. Of the 12,660 suppliers who completed Volkswagen’s self assessment survey, only 65 scored themselves at a “C” or below. Over half gave themselves an “A”. But what these numbers and letters actually mean is “kind of a mystery”, explains Deberdt. In these companies’ reports “you might find an average score on child labor of 58 out of 63, but we have no idea what that means. They think that child labor can be expressed in binary terms: child or no child.”

It is sometimes possible to glean information on the outcomes of a company’s compliance mechanism. For instance, in 2022 Volkswagen received 145 human rights complaints about its suppliers. Of these, four resulted in the temporary blocking of a supplier, and Volkswagen admits that it has yet to investigate over a third of the complaints.

Dutch automaker Stellantis is the world’s fifth largest vehicle producer by sales. It owns the American Brands Jeep and Ram and the European brands Fiat, Peugeot, Citroen, and Maserati, among others. In 2022, Stellantis sold 5.8 million vehicles and brought in €179bn of revenue. Like Volkswagen, Stellantis has invested heavily in EV development, and like Volkswagen, it has serious problems with its human rights compliance and reporting.

Last year, a group of twenty-two NGOs filed a case against Stellantis through the OECD’s “specific instance” system. In this mechanism, parties can file a complaint with the “national contact point” of an OECD member in an attempt to remedy some compliance failure. However, as the OECD’s website states, “NCPs are not courts: participation in the process is voluntary and the NCP does not have the authority to order any remedy measure.”

The case against Stellantis argues that the company has failed to provide transparent and detailed information on “their suppliers’ operations in cobalt mining sites in the Democratic Republic of Congo.”

In an interview conducted by the team with Luca Saltalamacchia, an environmental and human rights lawyer who filed the complaint against Stellantis, he defined this problem as structural, “It starts from the guidelines. If companies are not obliged by the law, they won’t do anything.”

Stellantis sources its battery materials from some of the largest Chinese cobalt miners in the DRC, in particular Huayou Cobalt. Huayou and another miner that it sources from, China Molybdenum, are accused of a litany of human rights abuses.

The human rights NGO RAID spoke with workers at these and other mines who reported, “being kicked, slapped, beaten with sticks, insulted, shouted at, or sometimes pulled around by their ear when they were not able to understand instructions in Mandarin.” One miner described seeing “a Chinese worker beating a Congolese worker with his helmet. When the Congolese worker tried to fight back, he was fired.”

Workers describe a workplace culture where safety protocols are just “rules on a wall” and where they are issued broken or worn-out protective equipment. Workers are also pressured to take risks, like running up scaffolding or being transported by forklift. One miner told investigators that “he knows of at least four people who had died during his time with the company.”

Photo Credit: Matti Blume

Huayou has also been accused of sourcing Cobalt from artisanal mines, where conditions are even worse. Artisanal mines are notorious for their use of child and slave labor. A report from Amnesty International found children as young as seven working in the mines, and UNICEF estimated that about 40,000 children were working in mines in just a single province.

Stellantis fails to mention any of these issues in its ESG reports. The company claims to oppose child labor and human rights abuses several times, yet it only acknowledge the practice the vague terms, stating there is a risk of “Incidents of child, forced or compulsory labor in the sub-tier supply chain“ The company fails to specify the nature or extent of their engagement on the topic, saying only that it “requires our direct supplier to address our standards and cascade them through the supply chain.”

Like Volkswagen, Stellantis does provide some data on supplier audits and site visits. In 2022, only 1% of suppliers were found to have “core non-compliance” with human rights issues. However, of the 147 onsite visits, auditors found 89 instances of core or critical human rights non-compliance. Stellantis mentions that suppliers who fail to meet required standards and do not improve may be excluded from the company’s supplier panel, but does not provide information on the number of suppliers who have faced exclusion. But even onsite audits show evident limits, as underlined by Deberdt: “high risk suppliers get audited only once a year for a maximum of two days. All the others, every three years”.

Stellantis and Volkswagen did not respond to requests for comment on their supply chain and their due diligence practices by the authors of this article.

The EU’s green taxonomy was supposed to stop companies from greenwashing, but the incentives to chase green money have proven too tempting: Bloomberg estimates that there are $35 trillion in “sustainable” investment funds, a figure that is expected to balloon to over $50 trillion within the next two years.

A new EU regulation on corporate disclosure could strengthen the reporting requirements for companies in their supply chain, but according to the Corporate Europe Observatory, the proposal has been “severely watered down by corporate lobbyists” and “a law originally intended to require companies to exercise ‘due diligence’ along their global supply chains has been left full of major loopholes.”

EVs are expected to be at the heart of the green transition because they reduce emissions and because the technologies that power them can be adapted to everything from heating buildings to sending airplanes around the planet.

And yet, the EU has built one of its core policies around a system which allows companies to call themselves green while working with suppliers who repeatedly engage in corrupt practices and support the systematic violation of human rights in one of the poorest countries in the world.

This is how, as Luca Bonaccorsi, a former member of the taxonomy’s advisory group, says, “a project that was meant to fight greenwashing has become an incredible tool to greenwash.”

This article is part of “Crossborder Journalism Campus”, an Erasmus+ project of the University of Gothenburg, Leipzig University, Science Po, and Centre de Formation des Journalistes in Paris. Additional Reporting: Heinrike Freytag, Simon Guichard, Bertrand Morain, Asmund Nottekaemper, Jakob Schmidt.

All images and footage used in this article are under a creative common license.

Video by Kelsey Lescop